Hello Everyone,

It has been a long summer and autumn. At the end of August, I moved to Cambridge where in September I started a graduate programme in Education and Policy Analysis (EPA) at Harvard’s Graduate School of Education (HGSE) - and this to be quite honest has kept me busy. But I am excited to pick things back up and share with you what I hope are new thoughts, stories and experiences.

Reflection

Global Lessons for Peace and Security - “Diversity, State-building and the Search for Peace” - United Nations

Ideas and Institutions

Reflection:

One of the courses I am enrolled in this semester is Developmental Psychology, taught by Professor Paul Harris. A key course requirement is that we participate in a research pool, and voluntarily serve as participants for any psychological research study or experiment being undertaken at Harvard. The intent behind this is twofold 1) to contribute to the department and help other graduate students complete their research, and 2) to provide students with an insight into experimental design from the perspective of a study participant.

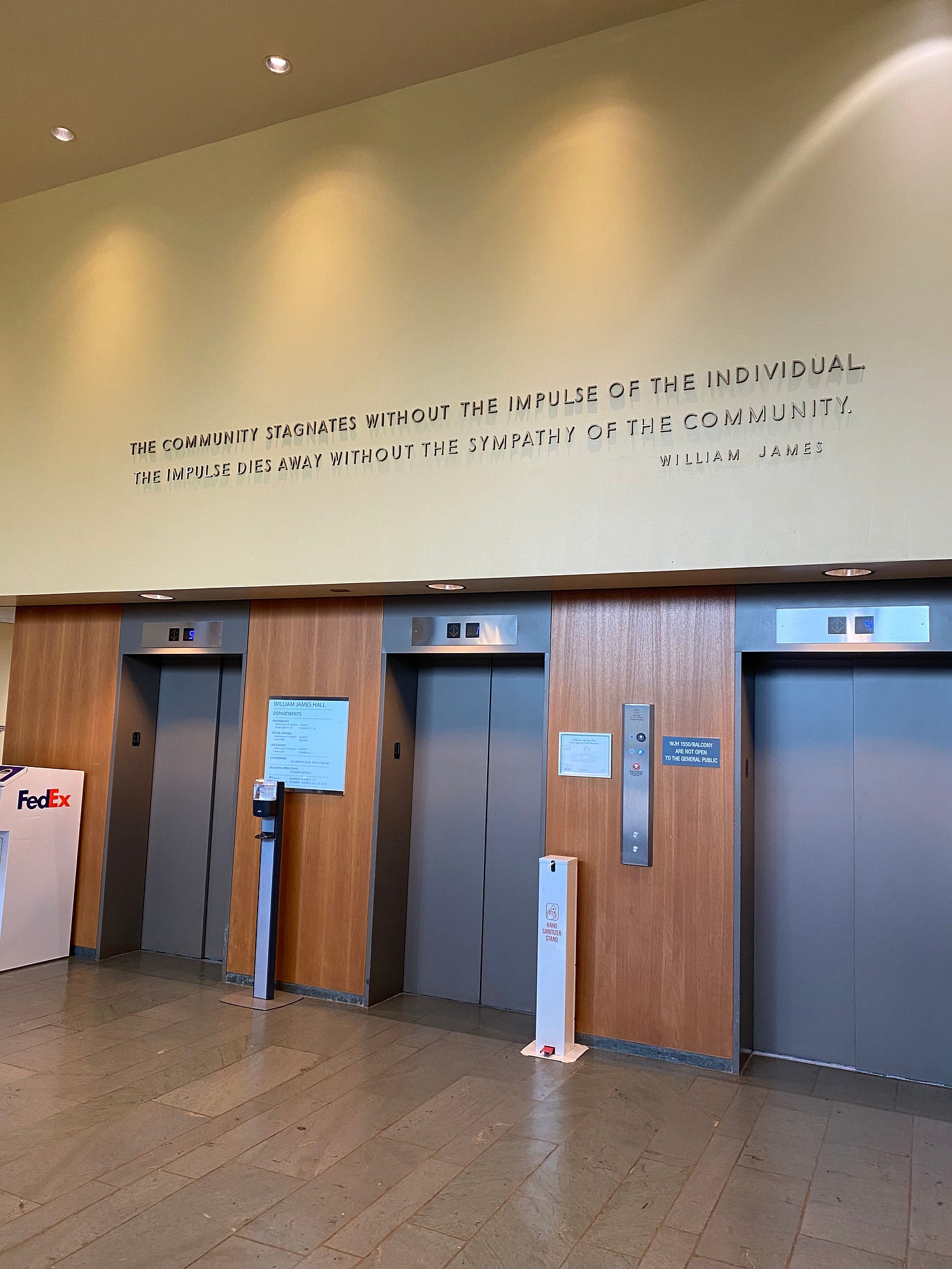

A few weeks ago I had the chance to participate in a study, and so I made the walk over to William James Hall, home of the university’s psychology department. As I entered the building’s lobby I saw this quote, which ran across the top of the building’s elevators:

As I think about this quote, and the spirit of gratitude brought on by Thanksgiving - I realise I have much to be thankful for. I am thankful for the various communities that have kept this impulse alive, be it my family back home, my community, and the new community of friends that I have found here.

However, Thanksgiving also provokes a more morbid thought. The arrival of winter, and the imminent end of another year. The days are getting shorter, the wind is getting colder and the last leaves have fallen from the branches. On days like this I am reminded that unlike the cyclical nature of the seasons, life has a finite end. While there will continue to be a spring and summer after each winter the same cannot be said for us. I only hope that I can enter that last winter knowing I made the most of my spring, summer, and fall.

“Life is less like a journey than it is a game of honeymoon bridge. In our twenties, when there is still so much time ahead of us, time that seems ample for a hundred indecisions, for a hundred visions and revisions--we draw a card, and we must decide right then and there whether to keep that card and discard the next, or discard the first card and keep the second. And before we know it, the deck has been played out and the decisions we have just made shape our lives for decades to come.” - Amor Towles, Rules of Civility

With each passing year, I cannot help but feel that my deck of cards has grown smaller, that the weight and gravity of each decision grows heavier, and that the choice to hold or discard each card grows more costly. But there is the small and precious comfort of knowing that unlike bridge I am not playing this game alone, that there is a community of support around me. With this realisation, I admit the burden is lifted, and the weight a little lighter. Life, unlike bridge is not a game one plays alone, and this provides some small satisfaction.

Global Lessons for Peace and Security - “Diversity, State-building and the Search for Peace” - United Nations

On October 12 2021 the United Nations Security Council hosted an open debate entitled “Diversity, State-Building and the Search for Peace” which sought to respond to the following question:

What successful experiences can be shared by states with regard to how they have built and sustained peace by embracing diversity and inclusion from the point of view of ethnic, gender, racial, regional, religious and other identities?

The format was that of a high-level open debate chaired by Kenya’s president, Uhuru Kenyatta. The resulting 23 page abstract is significant in serving as a useful set of criteria for the building and maintenance of peace. The list below is a summary of themes present in the report.

Eight Ingredients for Peace:

Robust Legal Framework and Institutions Must Work for All: One common theme was the need for robust legal frameworks and institutions that support and represent the interests of all. The representative from India emphasised “putting in place a strong legal framework as well as building credible institutions based on solid principles is critical.” The emphasis on credible institutions speaks to the importance of setting foundations for a peace that will outlast the lifetime of any individual actor.

Devolving Authority to Subnational Regions: A second theme was the realisation that achieving peace may involve the decentralisation of authority to subnational regions. The Secretary General remarked that countries, “emerging from years or even decades of instability cannot afford to ignore the views of broad swathes of the population and thereby risk stirring up future enmities. Governments must find new ways to move the population forward together in unity through constant dialogue while recognising and respecting differences, even if that means devolving certain areas of authority.”

Shared Understanding of Causes of Conflict: A third theme was the importance of achieving consensus on the root causes of conflict and tension. As explained by the representative from Rwanda, “peace is much more than the absence of violence. The precondition for sustainable peace is a shared understanding of the root causes of conflict by a broad range of stakeholders in society.”

Peace as an Ongoing and Human Process: The note also highlighted peace as an ongoing and human process, one which requires constant dialogue and work. “Peace building is not a purely technical enterprise. It is deeply political and human and must take into account the emotions and the memories that the various parties bring to the table.”

Failure to Manage Diversity: Representatives from most countries were quick to acknowledge that many of the root causes of conflict today have stemmed from the inability to successfully manage diversity. The debate’s concept note explained: “Humans have a need to belong: whether it is to a family, a village or town, a political party or to a religion, we are always part of a wider “we” that is central to how we cooperate, collaborate, compete and clash. We inhabit multiple identities and act on any one of them depending on the context and the perceived need. Throughout history, religious, ethnic, cultural, racial and other forms of identity have been negatively manipulated and turned into instruments for mobilization to compete for economic resources and political power. This, coupled with real or perceived marginalization and exclusion from political processes and economic resources, has generated violent demands for access or even led to separatist tendencies.”

Inclusive of Women Youth and Civil Society: As explained by the representative from Afghanistan the building of peace must be one that is inclusive of women. She explained, “the playbook for running today’s world was written primarily by men with men’s interests in mind. It presents men as the norm and women as the exception.In order to achieve that, we should make our political processes, structures and methods of work more responsive to women’s needs.”

Highlighting the Positive Experiences: Another theme was the importance of building on positive experiences. As noted by the representative from Norway, “we should draw on positive experiences by inclusivity being prioritised, from wherever they come, and use them to enhance our peace-building capabilities, especially in the United Nations context, where we can, and must, better utilize the tools that we have.”

Meaningful Inclusion: The last theme was that of meaningful inclusion, “inclusion must not be about tallying who is or is not at the negotiating table. It is instead about creating opportunities for people with a stake in sustaining peace to shape it. That is a central component in strengthening a society’s resilience against violence and armed conflict.”

Ideas and Institutions

There have been several times over the last few months that I have thought about the relationship between institutions and individuals, and I have grappled with two tensions that I am not sure how to resolve. The first is the tension between institutions and the values they produce, and the second is the tension between the forces of permanence and change.

Where do institutions come from? Douglass North in his 1993 Nobel Prize Lecture Speech observes,

Institutions form the incentive structure of society...the learning embodied in individuals, groups, and societies that is cumulative through time and

passed on intergenerationaly by the culture of society...are the humanly devised constraints that structure human interaction.

He goes on to explain:

“The relationship between mental models and institutions is an intimate one. Mental models are the internal representations that individual cognitive systems create to interpret the environment; institutions are the external (to the mind) mechanisms individuals create to structure and order the environment.”

The institution of family is one example. In Western society, the mental model of the nuclear family has defined the institution of family as consisting of the mother, father, and children. The extent to which this mental model of family is embedded in society and structures our environment is almost invisible. It is mirrored in the four door family sedan, the family style seating at restaurants, family discounts at the grocery store or restaurants, family targeted movies and the option on your Netflix account for “family friendly” TV shows. The point being that the more invisible an institution is, the more embedded in society it is, and the harder it is to change.

And yet, as David Brook’s points out in his article The Nuclear Family Was a Mistake this mental model of family is slowly shifting. He notes that the idea of the nuclear family in “Western” society while only a relatively recent phenomenon has fundamentally been changed by forces of demographic change, immigration, migration, economic stability, and larger cultural and social forces and attitudes of individualism, fulfilment, and purpose.

The stability of the family as an institution, relies on our capacity to re-invigorate the mental models of family so that they speak with significance to the new realities in which we find ourselves. If we can root the idea of family in a mental model makes sense of the changes in our external environment, the institution of family will live on.

The second challenge that is that between permanence and change.

One of the key advantages of institutions is that they give form to ideas, ethics and values that, by virtue of their institutionalisation will last beyond an individual lifetime. Yet while we require the stability of institutions, there is also a need for institutions to remain flexible, to adapt to the needs and contexts of the time without compromising the values and ethics upon which they were built. We also need to acknowledge the constraint of path dependence on institutions; that with each passing day the ability of institutions to react to change is limited by the choices they have made in the past, and so the past weighs ominously on an institutions ability to navigate the present and the future. Given these challenges what can institutions and the individuals in them do?

It seems then, that institutions and individuals must walk a fine balance. Remaining true to the values and ethics upon which they were built, but also having the courage and creativity to apply these values to the fluidity of contexts in which institutions find themselves.

Cornel West, when speaking of Harvard as an institution signals the very danger institutions face should they loose sight of the foundations upon which they were built. Institutions which no longer speak with ethical relevance to the societies in which they find themselves, risk, slipping “down the slope of self-institutional idolatry.” One can read his remark below as applicable to any institution, not just Harvard.

“If Harvard slips down the slope of self-institutional idolatry and loses sight of the best of its past and its present,” then the True Harvard will be subsumed. Left behind, West continues, will be “an empty institution obsessed with itself, dishing out different kinds of status, but the excitement, the vitality will be gone.”

Thank you for reading, and until next week.

FK